16 Percy Circus, St Pancras — 1905

A REVOLUTION IN ST PANCRAS SOUTH

![]()

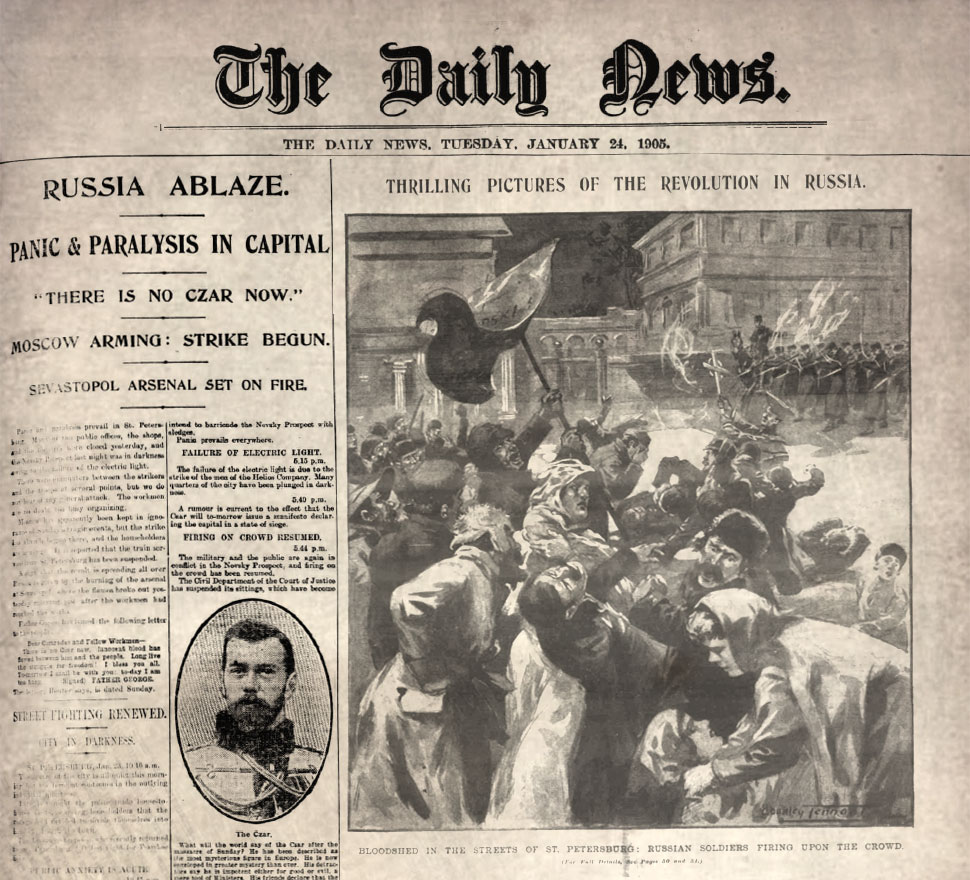

Lenin arrived in London, via Berlin, at the back-end of April 1905 for the 3rd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. Little is known about the congress, shrouded as it was in the utmost secrecy. The first revolution in Russia had got underway in January of 1905 and the two-week summit in London between April 22nd and May 10th would just about coincide with a violent, month-long mutiny breaking out on the Imperial Russian battleship, Potemkin (June 1905). The general feeling at the congress was that conditions were now at fever-pitch. In her 1930 memoirs, Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya described how the third congress ‘bore quite a different physiognomy’ to those held previously. Definition had been brought to the revolutionary organisations in Russia and these were taking the form of ‘illegal committees working under drastically difficult conditions of secrecy’. [1] Krupskaya also recalls that plans to arm the Petrograd workers were based around a massive haul of weapons to be purchased and smuggled into Russia from England on the London steamship, SS John Grafton, and to be crewed by East End and Whitechapel sailors. And although the plans proved fruitless (the ship was mysteriously wrecked just off the Finnish coast carrying 5,000 rifles and 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition), the confidence of trusted parties was more aggressively sought than before. [2] A raid on the party’s Central Committee had just taken place at the home of Leonid Andreyev in Moscow, and those members who were still at liberty to travel were instructed to reconvene in London. The identity of the venues was cloaked in secrecy for a reason.

But that doesn’t mean to say there aren’t some clues.

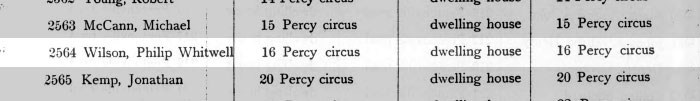

The address that Lenin used during his stay in London for the 3rd Congress was 16 Percy Circus in the Clerkenwell district.[3] The property was located minutes around the corner from Holford Square where Lenin had stayed during his first visit in 1902. [4] Today you’ll find it sporting a respectable blue heritage plaque, just across the road from the Travelodge Royal Scot. The area at the time of Lenin’s visit was set out on a south-facing embankment in a classical layout; a handsome arrangement of Squares and gardens offset by various rectangles. The roads here were wide and generous, quite different from others in the city. The houses were tall and impressive and the air was good.

When Vladimir Lenin lodged here in 1905, the property was the family home of parliamentary journalist and Liberal MP, Philip Whitwell Wilson.[5] Wilson was to run successfully for St Pancras South in 1906 as a Radical and Liberal candidate and had the same knightly earnestness (if not the looks and the charm) as the young Victor Grayson. Wilson had been unanimously adopted as candidate in January 1905 and came from a well known family in Kendal in the Lake District.[6] Interestingly, the former editor of Granta was one of four staff writers at the Daily News standing as candidates in London that year. In May 1905, just one year before being elected MP for St Pancras South, Philip Whitwell Wilson let Lenin use his home at 16 Percy Circus. [7]

![]()

In May 1905, just one year before being elected MP for St Pancras South, Philip Whitwell Wilson let Lenin use his home at 16 Percy Circus

Why historians have neglected to mention the part played by Philip Whitwell Wilson in Lenin’s early revolutionary activities remains a mystery. That a soon-to-be-serving Member of Parliament played host to a suspected terrorist at the height of an ongoing revolution just has to be worthy of mention, but to date, it’s escaped the attention of everyone. And this is a shame, as Wilson’s generous input might yet offer a clue to a mystery that has long since baffled academics: which venues did Lenin and the Revolutionaries use for the 3rd Congress? And the reason why it might offer a clue is fairly straightforward: Philip Whitwell Wilson was a senior council member of Whitefield’s Central Mission — something of a dynamo among the close-knit circle of churches in Central London offering refuge to the Russian exiles.

The mission, Nonconformist/Congregationalist in outlook and practice, had been set-up on Tottenham Court Road by Liberal MP and Minister, Charles Silvester Horne, after a donation of £8,000 from Mrs Elizabeth Rylands, wife of Manchester textile millionaire and philanthropist, Sir John Rylands in 1903. The mission, also known as Tottenham Court Road Chapel served under the auspices of the London Society Missions. The missions’ chief representative in Russia had been Stepney Minister, Edward Stallybrass, whose missions in Irkutsk and Selenginsk served to ‘correct’ the ungodly ways of the Mongol-descended Buryats.

In Herbert T. Fitch’s Traitors Within (1933), the former Special Branch detective describes a passionate flurry of smaller meetings taking place at three public houses in the Islington area. A steady roll call of biographers, academics and unscrupulous pub managers have put forward a handful of likely candidates over the years: The Crown and Woolpack on Clerkenwell Green, Walter Brett’s The Duke of Sussex at 106 Islington High Street; William J. Reed’s The Cock Tavern, 27 Great Portland Street and The White Lion, 25 Islington High Street. But as it was various East End Missions that had provided venues for the 2nd and 5th RSDLP Congress, it seems plausible that Wilson and Horne’s chapel on Tottenham Court Road may also have been among the handful venues used in addition to the Islington pubs in April and May that year. And if it wasn’t the Whitefield Central Mission, then we could well be looking at other Wilson-related venues like the Liberal and Radical Club at Grafton Lodge on Prince of Wales Road, or Cleveland Hall in Fitzroy Square. Cleveland Hall fits the bill just nicely as it is where Kropotkin had attended a meeting of international revolutionists in February 1887. By 1905 the hall had been taken over by Carmarthen’s Hugh Price Hughes of West London Methodist Mission, so the Police may have been looking elsewhere.

![]()

Why Was Lenin Boarding with Wilson at Percy Circus?

CHANGE BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY

![]()

Compared with the 2nd and 5th Congresses, the 3rd Congress came together in a fairly improvised but no less blistering fashion. The series of meetings had been initiated by Father Georgy Gapon, the Russian Orthodox priest who’d led January’s Bloody Sunday demonstration in St Petersburg. The massacre that ensued set in motion a remarkable chain of events that would later be aggregated and repackaged as Russia’s ‘1905 Revolution’. Some six weeks later in March, Father Gapon escaped to London and in April, the 33 year-old leader of the Russian Worker’s Club organized a series of emergency meetings that would bring together all the principal Russian revolutionary groups. The meetings had been expedited in part by the arrest of Leonid Andreyev, Evgeny Chirikov, Ivan Bunin, Stepan Skitalets and other members of the Sreda literary circle in the last week of February that year. The circle, which included several members of the RSDLP’s Central Committee and the author Maxim Gorky, had been questioned over the assassination of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich outside the Kremlin Palace, just days before.[8] The assassin was Ivan Kalyayev, aspiring poet and fringe member of the group. As a response the plans for the Congress were switched from Russia to London, whose Police, in contrast to those in France and Germany, had no formal relationship with Russia’s ‘secret’ police, the Okhrana.

During this period Gapon’s mood is known to have changed from one of peaceful action to ‘change by any means necessary’. Gapon’s meeting with Lenin in Geneva in the week immediately prior to the Bloody Sunday demonstration (January 22nd) was the clearest indication yet that ‘the moment of open struggle for Russia’s masses’ was fast approaching. [9]

The eighteen organisations invited to Comrade Gapon’s conference included The Socialist-Revolutionary Party, the Vperyod R.S.D.L.P, the Iskra R.S.D.L.P, the Polish Socialist Party, the Lettish Social-Democratic Labour Party and the Bund.[10] Gapon met Lenin on the 3rd day of the Congress (May 14th OS — April 27th NS) which saw the so-called ‘Council of Reform’ draw up a series of uncompromising demands: the immediate release of all political and religious prisoners, the creation of a republic with freedom of speech and free press, an autonomous government for Finland and the ultimate establishment of a democratic federation for the Caucasus. [11]

For the duration of the congress, Anarcho-Socialist Rudolf Rocker provided Gapon with full run of his home in Mile End, Stepney Green. The address was 33 Dunstan House. Just two months later Dunstan House would also provide refuge to the fugitive leader of the Potemkin Mutiny, Afanasi Matushenko. There were additional claims in the Manchester Courier and Dundee Courier on May 1st that Gapon had also stayed in Harrow and Ravenscourt Park — a favoured meeting place for William Morris, Dora Montefiore (who lived at nearby Upper Mall), Sergey Stepniak (Society of Friends of Russian Freedom) and the early Socialists. [12] Just a few years earlier, British Police had raided a flat at 16 Westcroft Square, Ravenscourt Park, printing office of the Revolutionary archivist (and detective), Vladimir Burtsev.[13]

Wilson’s colleague at the London Daily News, David Soskice also claims to have sheltered Gapon at his home at 90 Brook Green, Hammersmith — a home that Soskice shared with his mother-in-law, Catherine Hueffer, wife and model of Pre-Raphaelite artist, Ford Madox Brown and mother of Parade’s End novelist, Ford Madox Ford.[14]

Henry Noel Brailsford

A PASSPORT, AN EXPLOSION, AN ARREST

![]()

The man widely regarded as Gapon’s ‘campaign manager’ in London was Henry Noel Brailsford and like Lenin’s host, Philip Whitwell Wilson, Brailsford was a senior journalist at the London Daily News. Wilson and Brailsford also served on Parliament’s Balkan Committee, formed in 1903 as a result of escalating tensions (and complete ignorance) over Macedonia. The Committee was chaired by Scottish firebrand, James Bryce MP, who, like Grayson, had honed his oratory at Owens College, Manchester. The Man Who Was Thursday novelist, G.K. Chesterton also sat on the committee. Two years after the passport and Gapon dramas, Brailsford would seek funding for Lenin and attendees of the 5th Congress of the RSDLP. [15] The generous donor on that occasion was American Soap Magnate, Joseph Fels, whose market-leading Fels-Naptha Soap was based around a hydrocarbon mix of Russian Crude Oil and Coal Tar. [16] The compound also formed the basis of many early explosive devices. Just 12-months prior to the Congress, Joseph Fels had been sued by the Mercantile Marine Company when their steamer, the SS Haverford, exploded on entering the docks at Liverpool carrying 90,000 pounds of Fels-Naptha Soap. A total of fourteen men were killed. [17] Interestingly, Lenin’s 5th Congress associate, Rosa Luxemburg identified Russian naphtha as the “most important and vital economic resources of the revolution”. [18] Luxemburg was one of the many delegates that accepted the £1700 loan from Fels (about £150,000 in today’s money). Josef Stalin, the young bandit who pretty much held the Naphtha refineries to ransom during his time in Baku as strike leader and extortionist, was another (Stalin’s protection racket played a key role in launching and resolving the strikes at Caucasus Naphtha Company and the Baku Naphtha Company in February that same year, briefly driving up the price of Naphtha).

That the Daily News provided an exhaustive review of Gapon’s ‘Story of My Life’, suggests there were strong lines of communication between the paper, it’s editor Alfred George Gardiner, and revolutionary poster-boy, Father Gapon.[19] Gapon’s book, purported to have been written by Gapon but generally accepted to have been ghost-written by the Daily News’ Brailsford, G.H. Perris and David Soskice, was published in November 1905 by Chapman and Hall. Again, it’s an interesting link as it was Chapman and Hall who’d been the first to publish Charles Dickens, the founding editor of the Daily News (the company had also just published Bennett Burleigh’s Empire of the East: Japan and Russia at War 1904-1905). The fact that the newspaper’s foremost Russian contributor, Theodore Rothstein, would end up serving as Soviet Ambassador in the 1920s may also indicate deeper level of collusion, as Lenin is known to have made frequent visits to Rothstein’s home in Clapton Square that same year. The house was owned by Rothstein’s father-in-law, Isaak Kahan, a Russian-born shipping and banking broker whose student daughter Zelda would become a founding member of both the British Socialist Party and the CPGB. [20] Surveillance had been placed on Rothstein in Britain as early as 1903 when a report by Leonid Ratayev recorded the sometime newsman shuttling between his home at Clapham Square and 15 Augustus Road, the printing- offices of the Russian Free Fund, which was at that time under the supervision of Leon Goldenberg who had recently re-located from New York.[21]

Lenin lodging with Rothstein’s Daily News colleague, Philip Whitwell Wilson at 16 Percy Circus might well be viewed in this context.

Sadly the relationship between Gapon and The Daily News didn’t end as positively as it had begun. Just as he was securing funds for Gapon’s return to Russia, Brailsford was charged by Police with passport fraud. The Metropolitan Police had found Brailsford and Manchester-based actor, Arthur Muir McCulloch (formerly of 29 Percy Street) having fraudulently obtained three English passports for use by Russian exiles, including one for Maximilian Schweitzer who had died in an explosion at the Hotel Bristol in St Petersburg in February that year. [22] According to friends, Brailsford was a bit of a soft-touch in this respect, Wilson Harris later writing that “on Brailsford, anyone who was in any sense revolutionary had an a priori claim”.[23]

The passport plot itself dated back to Father Gapon’s Bloody Sunday demonstration when Boris Markov, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party’s Battle Operation had been arrested in St Petersburg. It’s believed Markov was in town to coordinate an attack on several targets including Grand Duke Alexandrovich and Governor-General, Alexander Trepov. The plot was uncovered when the bomb-maker, Schveitser blew himself up prematurely at the Hotel Bristol. The Police claimed that the dead man possessed a passport in the name of McCulloch, and the actor and reporter were duly arrested by Police.

Brailsford’s arrest would almost certainly have been perceived as a serious blow to the Balkan Committee and the Liberals’ ongoing relief efforts in Macedonia. Brailsford admitted full responsibility for his actions, confessing that he had been asked by ‘someone he knew connected with the Russian Revolutionary Movement’ to obtain passports on his behalf. The man, a leading member of Russia’s Constitutional Movement and currently living in exile on the continent, had assured Brailsford that the passports were to be used as part of a peaceful demonstration. Brailsford and the Foreign Office refused repeatedly to name the man although Brailsford’s biographer, F.M. Levanthal would later point the finger at his friend, David Soskice. [24] The passport had been signed by Lord Lansdowne, the man who had also just signed the landmark Anglo-Japanese Alliance Trade Agreement at his home in 1903.

Did Lansdowne and the Foreign Office play a clandestine role in Lenin and Gapon’s 1905 bid to supply rifles and ammunition to the Revolutionaries in Russia? It’s certainly possible. At the time the plot was hatched, Russia was not only at war with Britain’s new trading partner Japan, it was also ramping-up plans to set-up naval bases in the Persian Gulf. On learning of these plans, Lansdowne made vociferous objections in Parliament, declaring ‘without hesitation that his Majesty’s Government would regard the establishment of a naval base or any other fortified port in the Persian Gulf … a very grave menace to British interests’. [25] The Dogger Bank Incident of October 1904, when the Russian Imperial Navy had fired on a British fishing trawler, killing three British workers, had breathed fresh life into those concerns, and it’s curious to note that that Schweitzer’s fraudulent passport had been issued to McCulloch and signed by Lansdowne at the Foreign Office that same month (October 28th, 1904).

The fact that the SS John Grafton is alleged to have been purchased for the purpose by Japanese army officer and intelligence agent Akashi Motojiro, makes the whole thing quite plausible. And as far as diplomacy with Japan was concerned, the move would certainly have been a positive one.

Father Georgy Gapon, the priest who had originally called for the 1905 congress in London, survived until March 28th 1906 (O.S) when he is alleged to have been murdered at a villa in Oserki, just outside St. Petersburg, by Socialist Revolutionary and alleged spy, Pinchas Rutenberg — also believed to have been in hiding in London’s West End.[26] Gapon’s death coincided with the mysterious suicide of Helene de Krebel, aka Marie Derval, at the Liffen’s Hotel in Pimlico, just a short walk from the Russian Embassy at Chesham Place. By a strange coincidence, the hotel and its owner, insurance agent George Liffen, featured in another mysterious ‘closed room’ suicide in 1911 when 46-year-old Jahanna Smerecka was discovered with gunshot wounds to her head in her guest room. Baptismal and marriage certificates, written in Russian, were found in her possession. The woman had married in Chernivtsi in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (present day Ukraine) and her death came shortly after the arrest of Fraulein Trombooke who had been spying for Russia’s Imperial Forces in Austria, most likely under the supervision of Alfred Redl.

Like Krebel, Smerecka had spent the previous weeks in America, and also like Krebel Police found a handful of mysterious keys wrapped in brown paper in a ‘secret pocket’ of her coat. [27] The following year George Liffen, now proud owner of the ‘comfortable and convenient’ Alexandra Hotel in Hyde Park Corner, was unfortunate enough to suffer another foreign casualty in his charge, when newly arrived Italian, Gino Masini was found gassed in his room. [28] At the Westminster inquest no parallel was drawn with the previous suicides on his premises, but the danger of ‘loose taps’ was raised. Liffen was able to reassure the jury that the ‘faulty gas taps’ had ‘been seen to already’ and no further questions were asked. [29]

In his 1933 memoirs Special Branch detective Herbert Fitch describes Krebel as the mistress of Georgian anarchist, Warlaam Tcherkesoff (Varlam Cherkezishvili), a close friend of Sergey Stepniak and an associate of Prince Kropotkin and Rudolf Rocker. The middle-aged woman was found dead in her room on March 14th 1906. It is alleged she had been hounded to her death by revolutionaries who’d suspected her of spying and had been pursuing her actively across America and Europe for some two years or more. A sentence of death was hanging over her. The waiter at the hotel claimed that on the morning of the 14th Krebel had received a letter ‘which upset her terribly’ and had locked herself in her room. She had ‘wept, shrieked aloud and walked the room as one demented’.

Three weeks later, revolutionary poster-boy, Georgy Gapon was also dead.

But the twists didn’t end there.

Just a month before his death, Georgy’s brother, Sergey Gapon, a captain in the Russian army at Port Arthur in China, was arrested for being drunk and disorderly by Police in Eastbourne. The date was March 3rd 1906.[30] After a short hearing it was decided that Sergey would be expelled under the Aliens Act and was removed to Lewes Prison to await deportation. Shortly after his release from Lewes Prison, Sergey Gapon was also dead. His body had been pulled from the sea at Hastings on the very day that Helene de Krebel had checked into the Liffen’s Hotel in Pimlico.[31]

Tsarist Spies in London and Hastings

SIMILIA SIMILIBUS CURANTUR

![]()

On January 27th 1905 Wilson’s Daily News had announced that a “special staff of Russian police spies” had arrived in London.[32] The following month, the New York Times and The Daily Express would publish a more detailed report based on an interview with Vladimir Burtsev’s colleague in Paris, Ilya Alfonsovich Rubanovich claiming much the same thing only reiterating the support that Tsarist Spies were receiving from Sir William Melville, newly appointed head of counter intelligence in the War Office’s ‘MO3’ — a precursor to Britain’s Secret Service Bureau. The Daily News story emerged shortly after the announcement that Major General Trepoff, the late Chief of Police in Moscow had just been appointed Governor General of St Petersburg. [33] Ever since taking a hard-line approach with student activists back in 1897, the General had gained an unfavourable reputation for placing large numbers of agent provocateurs in workers’ movements, or as The Times of London described it, pursuing a doctrine of ‘Similia similibus curantur’.[34] That Trepoff’s appointment coincided with the worker’s march organized by Father Gapon would almost surely have grabbed the attention of Revolutionary ‘Sherlock Holmes’ Vladimir Burtsev, who was suspicious of practically everything and everybody. [35]

Burtsev’s friend Alexsei Teplov, Secretary of the newly expanded Russian Free Library on Princelett Road, responded to the news of General Trepoff’s appointment by saying it was his solemn conviction that the massacre of the striking workers on ‘Bloody Sunday’ had been deliberately prearranged. It was, he went on, all part of a careful scheme for crushing the desire for political and economic change. One of the spies had already been recognised as agent provocateur. To Burtsev’s credit, most of the revolutionaries in his London circle, including Teplov, had been trained in the skills of spy-spotting. To illustrate the point, Mr Teplov boasted of the ease with which the circle of revolutionaries was outwitting the Tsarist spies. They were used to spies, he told reporters. The names, descriptions, addresses and doings of every one of them were known to the secret police and he laughed as recalled some of his own experiences. “I never move around but am followed,” he said. “Even if I go away for a little fresh air, I put Russia to the expense of having me accompanied.”

In a column titled, ‘Comedy in Hastings’, Teplov went on to describe how he had visited Hastings the previous summer and how the Tsarist police had followed him, ‘evidently’ because he had “something very deep at hand.” During his time in Hastings he had spared a few hours on the pier, just yards from the pier-side groyne where Sergey Gapon’s body had been washed. So mysterious had been his activities here that Teplov described how reinforcements had been sent from London. Another night after a watching a concert at the White Rock bandstand opposite the pier, Teplov recalled slipping out from the crowd and losing himself in a ‘dark corner’ just for fun. Within minutes the Tsarist spies were running up and down the length of the pier ‘in the most excited fashion’.

Twenty-four hours after the report was published, Teplov, David Soskice, Lazar Goldenberg, Warlaam Tcherkesoff and Nikolai Tchaikovsky would chair a meeting at Whitechapel’s Wonderland Theatre to discuss the threat and the challenges posed by Trepov’s ‘special staff’ of Police spies. The event had been arranged by the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom. Over 3000 people were alleged to have attended that night, including English Society President Robert Spence, Balliol College’s George Meredith and Alfred George Gardiner — Philip Whitwell-Wilson’s editor at the Daily News. The committee duly announced that a new fund was being set up to collect and administer support for families of those killed or injured in the St. Petersburg demonstration with Spence, Gardiner and Meredith elected as treasurers. Another meeting was pencilled in for the Sunday. [36] The man most likely leading the pack of spies was Edgar Farce, the tenacious French detective deployed in Britain by Rachkovsky at the Okhrana’s Paris office. It may be recalled that Farce had been hunkered down at Belbow Road in Hammersmith, just a few minutes’ walk from revolutionaries Alexei Aladin on Sulgrave Road and Felix Volkovsky and Leon Goldenberg at the Society of Friends base on Augustus Road. Lenin wouldn’t arrive in London for another few months, but when he did, it was in the Percy Circus lodgings arranged by Nikolai Alekseev, Lenin’s London Lieutenant. This was gearing up to be quite a momentous year so the increase in spy activity was only to be expected.

What business Teplov had in Hastings that week was never explored, but given the resort’s significance in the publishing activities of Russian exiles Alexei Sheftel and Jakoff Prelooker, it seems inevitable that Teplov was mixing no small amount of business with pleasure, perhaps even relaying messages beneath the convenient drone of the band.[37]

Whether Melville had some of his own men on the ground in Hastings isn’t known but it is interesting that the last man to see Serge Gapon alive in Hastings the following year was Charles Crossley, a senior representative of the Citizen’s National League, a patriotic union of grievous anti-Socialists. Crossley, a visitor from London, had been seen talking to Gapon at the pier the previous evening. The man told them he was a captain in the Tsar’s Imperial Guard and on his way to visit the Russian Consul in Folkestone. Crossley and his brother were believed to be the last men to speak to the troubled deserter. [38] Two days later, Crossley featured in another report in the press, this time announcing the formation of a National Anti-Socialist League at the Junior Carlton Club in London’s Pall Mall. The meeting was held under the presidency of Thomas Orde Hastings Lees, Honorary Secretary of ‘prepper’ association, The National Service League.[39] Among the League’s most active and influential members was Sir Walter Long, whose memorandum in January 1919 requesting direct action against domestic terrorist threats led to the formation of the Secret Service Committee.[40]

Ilya Alfonsovich Rubanovich, speaking to the New York Times on March 5th 1905 just weeks after Teplov’s farcical account of spies in the London Daily News, expressed his belief that there were dozens of Tsarist spies in London and that many of them may have been British. Although he rejected any suggestion that the British Police were colluding formally with their Tsarist counterparts, Rubanovich claimed that a special political department at Scotland Yard, who had an “inborn prejudice” against the Socialists, frequently passed on discreet “indications” to the Russians. Speaking from his fifth-floor apartment at the back of the Panthéon in the old Latin Quarter of Paris, Rubanovich confided that the Tsarist Secret Police had a significant number of its spies permanently stationed around its ports. Managing its operations in England was a woman. She had a team of around sixty or seventy men and that several of them were English.[41] The editor of the Tribune Russe went on to explain how the political department in England dated from the time of the old Fenian outrages, when New York’s Clan na Gael were alleged to have been colluding with Russian Nihilists in a number of dynamite plots. The interview was duly repeated in the Daily Express.[42]

The head of Russia’s Secret in London was a woman? Was there any chance that Rubanovich was talking about Helene de Krebel, the woman murdered at the Liffen’s Hotel in Pimlico in March 1906? It would certainly make sense. The Liffen Hotel was on Gillingham Street, just around the corner from the Imperial Russian Embassy at 30-31 Chesham Place. As we have learned already, the manager of the hotel, George Liffen had featured in several other locked-room mysteries, including one at the Alexandra Hotel. Father Gapon’s brother was pulled from the sea in Hastings on March 11th 1906 and de Krebele had died in the hotel room on the 12th, the following day. Father Gapon’s own murder would take place at the end of the month in Russia. The Russian Embassy had done all the running on the Krebele case, interviewing the hotel proprietor and obtaining what remained of her luggage.

Just twelve weeks earlier British playwright William Toynbee had showcased his new play The Firefly at La Scala Theatre. At the centre of the plot was a revolutionary heroine who saves herself from a lifetime of exile in Siberia by spying for the Tsarist police in London. Once in England her mission is to gain the confidence of the British Foreign Office and steal some government papers. The mission falls apart when the heroine falls in love with a Foreign Office employee whose father is the British Ambassador in Paris. The play explores her life as she moves between various hotels in Mayfair.[43]

Toynbee Hall

WILSON’S FIRST HAND EXPERIENCE OF BOLSHEVISM

![]()

There’s an interesting overlap here, as the brother of The Firefly’s author, Williams Toynbee was social reformer and philanthropist Arnold Toynbee, one of the most active and visible protagonists of the turn of the century Settlement Movement — a brave and ambitious relief-based programme which attempted to narrow the various boundaries that existed between rich and poor. Among the group’s most enthusiastic supporters were Lenin’s Percy Circus host, Philip Whitwell Wilson, who was quick to acknowledge the movement’s “instinctively American” values, and Soviet architect and educator, Alexander Zelenko who was to launch a Settlement branch in Moscow later that year. In his 1919 article, The Barnetts of Toynbee Hall for New York’s Outlook magazine, Wilson described his time at the group’s first practice station, Toynbee Hall in London’s cruelly insolvent Whitechapel district. In 1903 the Hall had become something of a university settlement, gradually changing from “a criminal haunt to the home of eager, upward-striving Judaism”. It was here that Wilson’s close encounters with “irregularly unemployed, the drink-ridden unemployable and the sweated worker” occurred during his twice weekly stints chairing its boisterous debates “formal and informal” with men of various occupations and grievances. [44] Writing in 1903, Wilson explained how the growth and spread of industry had given rise to a “disintegrating process” that had a created a “physical gulf, miles broad” between the slum dwellers and their wealthy neighbours. The ‘Settlement Ideal’ sought to change all that. Toynbee Hall was a place where the “dock labourer or the unmanageable emissary of the Social Democratic Foundation could “unburden his mind of ideas so extraordinarily shrewd if also perverse”, that constituted “a wholly unlooked-for liberal education”.[45]

Between 1903 and 1905 Wilson claims he had taken lessons “at first hand in what is now called Bolshevism”. For months he had “argued and wrestled with the very type which has blossomed into Lenine and Trotsky”. The things that the world was hearing now were for him, old news. [46]

In the years 1902 to 1903, Wilson had lived at Toynbee Hall surrounded by Canon Barnett’s “Cosmopolitan aliens” and the high-minded Ruskinian aestheticism they all aspired to. Wilson’s knowledge of Lenin and Trotsky clearly dated back to this period, so is it possible that his first encounter with his famous lodger dated back to his time at Toynbee Hall? Wilson’s editor, Alfred George Gardiner was certainly close to both the ‘settlers’ at Toynbee Hall and Lenin’s friends and supporters at the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom, where Gardiner now sat as treasurer as the hastily organised Russian Relief Fund.[47] The idea was certainly plausible.

Wilson. Samuel Barnett seated

Lenin himself had spoken Toynbee Hall during his first visit to London in 1902. The “short and stiffly built man with a short neck and large head” had addressed a Thursday ‘smoking debate’ on British Foreign Policy, in which he declared that the people of London’s East End knew little and cared even less for the Imperial exploits of its government.[48] Dean Robinson, Head of Oxford’s Balliol House and a senior director at Toynbee Hall would later invite him back for a spot of tea and an English muffin. Here he was alleged to have continued his tirades against British Imperialism and the indefatigable opioid that was organized religion.[49]British Labour MP George Lansbury, who arranged for Joseph Fels to pay Lenin and Stalin’s travel expenses at the end of the Fifth Congress of the RSDLP in 1907, would later express the view that Toynbee Hall perpetuated rather than lessened class differences.

In July 1905, some several months prior to the performance of Toynbee’s play The Firefly, a member of the “Russian Revolutionary Committee” had told the London Evening Standard that there were known to be various women moving around in London court circles who were in the pay of the Russian Government. It was alleged that one of the women, who the committee member had met in Paris, had offered him 25,000 francs to hand over the names and addresses of all the revolutionary leaders and workers residing in Russia. She had later confessed to the committee leader that she was disgusted with the whole thing and was anxious to escape. The response of the Secret Service was that if she left their employment she would be shot. Curiously enough a short time later the same lady was found shot in a hotel room in Nice.[50] It may be worth pointing out that the rather sensational claims being made in the London Evening Standard coincided with the arrival of Lenin and other revolutionary leaders for the 3rd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party at the end of April. Part I of the revelations had appeared a few days earlier, in which the various revolutionary groups and their methods were described at length.[51]

Wilson’s passing encounters with Trotsky at Toynbee would take on an additional resonance after his move to New York as American correspondent for the London Daily News. In a curious twist, Wilson would end-up living just several hundred yards from Lenin’s 1905 host, Philip Whitwell Wilson from Louis C. Fraina, editor of The Class Struggle, and the man who perhaps did more than anybody to help Trotsky settle-in in New York during his three-month stay in the Bronx between January and March 1917. According to Wilson’s 1918 US draft card [52], he’d initially set-up base at 55 West 44th Street in Midtown Manhattan, but in just a short space of time he had bedded himself down at West 230 Street Spuyten Duyvil, the Bronx where he would remain quite happily until in his death in the 1950s. Just 10 minutes walk east was the Italian-born Fraina and his 35 year old common-law wife Jeanette D. Pearl, a chemist who had emigrated from Russia with her father Charles some thirty years before. The family’s first home at 2349 Pitkin Avenue in the Brownville district of Brooklyn put them within a five minute walk of hot-footed Hastings compositor, Alexei Sheftel on Sutter Avenue after his relocation to America in 1907. Within weeks of his arrival at 1522 Vyse Avenue (Bronx), Trotsky was writing articles for Fraina’s new journal, The New International, the organ of the Socialist Propaganda League. An ad run in Fraina’s sister journal The Class Struggle described the fortnightly paper as an “aggressive journal of action … to fight fighting”.

Just who was Helen de Krebele?

A FEMALE SPYMASTER IN LONDON

![]()

In July 1905, some several months prior to the performance of Toynbee’s play The Firefly, someone alleging to be “in close touch” with the “Russian Revolutionary Committee” had written in the London Evening Standard that there were known to be various women moving around in London court circles who were in the pay of the Russian Government.[53] It was alleged that one of the women, who the author had met in Paris, had offered him 25,000 francs to hand over the names and addresses of all the revolutionary leaders and workers residing in Russia. She had later confessed to the committee leader that she was disgusted with the whole thing and was anxious to escape. The response of the Secret Service was that if she left their employment she would be shot. Curiously enough a short time later the same lady was found shot in a hotel room in Nice. [54] It may be worth pointing out that the rather sensational claims being made in the London Evening Standard coincided with the arrival of Lenin and other revolutionary leaders for the 3rd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party at the end of April. Part I of the revelations had appeared a few days earlier, in which the various revolutionary groups and their methods were described at length. [55]

The mass of contradictions relating to the dead woman’s identity in the press, first linking her with American millionaire John P. Cushing and then with anarchist, Warlaam Tcherkesoff had simply obfuscated the matter and given them time. But maybe this had always been the point. The story being pushed was that the as then unidentified woman was the estranged wife of John P. Cushing. The story had taken root at the New York Herald. Its editor James Gordon Bennett Jnr. was based in Paris where the interview with Ilya A. Rubanovich had taken place. Bennett Jnr. had been a good friend of his Imperial Highness, the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, another Paris regular, the pair having met during the Duke’s arms-buying trip to New York in the 1870s, during which he entertained him at his Rhode Island yacht club. The Duke was to die in Paris after moving there after the assassination of his brother, the Tsar’s fifth son, the Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich in February 1905.

It wasn’t the first time that John P. Cushing’s utterly bizarre marital affairs had been in the papers. In August 1900 the Boston Globe had run a story about Cushing’s wife Laura, the woman thought to have been the dead woman in Pimlico. It seems the pair had married in Manhattan after a whirlwind romance in October 1894 after being introduction in theatrical circles. The problem for John was that his 27 year old wife had still been married to her first husband, Nathaniel Ward, a pool and billiard room owner with a passion for racing cars living in Brooklyn New York. His wife Laura Wolfe had been a pretty young actress with the Gilbert, Donnelly and Girard Theatre Company and the pair had married in haste some years before. The divorce that both parties thought they had not been recognised. Her father and mother in Newark, New Jersey, Philip and Louisa Wolfe, both born in Germany, appear to have known little of the second marriage.[56]

After the body of Helen de Krebel was found dead at the Liffen’s Hotel and rumours began to circulate that it was the ex-wife of John P. Cushing, a letter had been delivered to James Gordon Bennett Jnr. of the New York Herald in Paris, purportedly from the woman herself saying reports of her death in London had been ‘greatly exaggerated’. The writer of the letter would subsequently disappear leaving no trace of her whereabouts. The rumours had begun at the formal inquest, when it was mistakenly divulged that the body was that of Laura A. Cushing. The claim had been made by her sister Gertrude Wood, the wife of American speculator Harvey Wood and backed up in part by James Tweedie of the Anglo American Exchange. The coroner Mr Troutbeck wasn’t quite so convinced.

The young woman was eventually tracked down to an apartment near rue Saint-Honoré and her identity was established beyond all doubt. She even mentioned the issues relating to the irregularities of previous marriage and divorce from Nathaniel Ward. She had no idea why her sister had misidentified her as the dead woman and which had thus far baffled the courts. She did, however, relent that the pair had become estranged and the sister may have been confused by the reference to a deformed finger on the hand of the dead woman. She had left New York after receiving threats to her life and had sought the protection of Paris Police. [57] Like Bennett Jnr., it appears that John P. Cushing was familiar in yachting circles, his aristocratic grandfather, John Perkins Cushing having been a successful slave trader, opium smuggler and yacht racing champion.[58] In an extraordinary twist, it appears that the Grand Duke Alexis had enjoyed a breakfast reception at the 200 acre Belmont Estate, the home of his son John Gardiner Cushing shortly after his introduction to Paris-based editor James Gordon Bennett Jnr. in 1871. The Grand Duke would return to Belmont in 1872. [59]

One Other Curiosity

WAR & SOCIAL REVOLUTION

![]()

In the final week of April 1909, Lenin’s Clerkenwell and Iskra associate, Harry Quelch gave a talk at the Gaiety Theatre in Fife entitled, ‘War and the Social Revolution’. John Maclean, who became Bolshevik Consul in Glasgow in the post-revolution period, joined Quelch as speaker, as did George Gunn and Baile Cormie. Quelch warned of the dangers of war and the impact that war would have on the progress of the Social Revolution that was already underway in British Society. In Quelch’s estimation, war was the one safeguard of the capitalist system, and that the great burden and risk of war fell primarily on the working classes. War and its possibilities would hold back the Socialist Movement and hinder Social Revolution. Whilst capitalists could be heard deprecating war they were ‘all the time producing things that made war inevitable.’ [60]

In October 1915 Lenin’s 16 Percy Circus host, Philip Whitwell Wilson had used exactly the same incendiary phrase in an article published by The Fortnightly Review entitled War and the Social Revolution. And although he may not have arrived at the same bleak conclusion, the basic premise was just the same. In an extraordinary twist Wilson also divulged that much of what he was about to write was based on a ‘private conversation’ he had had with the recently deceased Lord Rothschild (April 1915). Wilson had been accused of abusing his parliamentary privilege in the past so this kind of candour wouldn’t be totally out of character, and it certainly might explain the polarity of views being offered in the finished article.

Was Wilson’s recycling of Quelch’s phrase a mere coincidence? I suspect not. Just as it probably wasn’t a coincidence that the phrase, and the complex payload that it carried, was recalibrated and re-served some twenty-five years later by Joseph Goebbels and the Nazi Party as part of their ongoing propaganda programme: Der Krieg Als Soziale Revolution (‘War as Social Revolution’). Under the Fascists, the appropriation of the phrase was a little easier to comprehend: the Nazis were promoting the idea that they were expressing the collective will of the people to bring about positive change through war. It was at least one thing they had in common with Lenin. With Wilson, there was a more meta-literary and meta-historical dimension in his use of the phrase. Superficially at least, Wilson was endorsing it, but dig a little deeper into the text and you’ll find he is deconstructing it. Wilson is addressing the phrase as part of a popular discourse. The intertextual elements force us to first recognise it, and by degrees, to challenge it. Our a priori understanding of the phrase is being gently transformed from within. Wilson is positing questions: what does ‘revolution’ really mean? And furthermore, how can it make any kind of lasting difference at a ‘social’ level? Under the Nazis, the recycling of the phrase was a disingenuous theft; a case of a bait and switch. Wilson was engaging with it on a more complex, semantic level. He was seeking to get right under the bonnet of the phrase and rip out its engine, not only seeking to alter its composition, but change the journey it might be taking. Whatever his intent, Wilson’s instinctive grasp of the rhetoric of Revolutionary Socialism, even if not it’s more practical applications, certainly suggests his time at Toynbee Hall, and his ambiguous proximity to Lenin in 1905, might have not been totally without impact on the direction his life was taking during the war and the post-war years.

So if Philip Whitwell Wilson wasn’t some communist revolutionary or Bolshevik, then what was he? Government spy? I can’t see it myself — certainly not at this stage although it’s inevitable that the more polished and theoretical émigrés like Lenin would have made them attractive allies in Britain’s ‘cold war’ with Tsarist Russia; the intelligence support we were offering Japan Japanese-Russo War, making them doubly appealing. Lenin’s recently published, ‘What is to be Done?’ had sought to transform the crude reactionary nature of revolutionary discourse into a more organized political consciousness and shape the Russian Social Democrats into a highly disciplined and centralized party that would serve to sharpen the resolve (and diminish the violence) of the Socialist Revolutionary movement. Vladimir Burtsev went so far as to speculate that Lenin himself had become a key figure in Russia (and Britain’s attempts) to suppress and pacify radical and political opposition among the Marxists. As Dr Robert Henderson points out in his 2020 book, The Spark that Lit the Revolution, Edgar Farce, the Okhrana’s top agent who was working with Special Branch detectives in Hammersmith, failed to make any reference to Lenin’s stay at 16 Percy Circus, despite the meticulousness he showed in logging and monitoring Lenin’s colleagues at neighbouring addresses. [61] Could this be an indication that Lenin was in London with the full cooperation of the British Secret Service? It’s unlikely, but not impossible. One of Wilson’ closest ‘settlement’ friends at both Camberwell and Toynbee Hall was fellow radical Liberal, Charles Masterman, who would eventually lead the War Propaganda Bureau at Wellington House, a ‘creative Intelligence’ exchange of sorts for Britain’s spies and propagandists. [62] It’s entirely possible that Wilson’s arrival in New York in the first week of January 1918 was linked in some way to the work of the Propaganda Bureau whose main brief now was to keep America in the war and get their support for the League of Nations.[63] By February 1917, however, the Propaganda Bureau was no longer headed by Masterman but by the cousin of his wife Susan, the 39 Steps novelist, John Buchan.[64] According to a statement published by the Daily News on January 5th 1918, his mission in America was to study the “great drama of America at War and present its powerful developments” to its readers. [65] However, there is perhaps no better illustration of his more coercive role there than an article that Wilson penned for the American Review of Reviews in July 1918, pushing the legitimacy of the League of Nations, probably upon the instruction of his old friend Lord Bryce on behalf of the soon-to-be formed Union of the League of Nations and its American counterpart, the League to Enforce Peace: “The future of the world depends on good relations between the United States of America and the family of peoples included within what is none to accurately called the British Empire.” Anticipating a wave of protest from America’s legion of Anti-Imperialists, Wilson issued the weakest of defences: “Today the British Empire exists solely on a basis of consent, and anyone can leave who wants to.” [66] Wilson may have been an agent, perhaps, but there was certainly nothing secret about it.

So if Wilson wasn’t a secret agent, was he just an interested and eager observer? I think that much goes without saying. Wilson’s time at Toynbee Hall and his faith in Barnett’s ideals would have been a compelling incentive, just as Lenin’s visit to Letchworth in 1902 suggests a no less curious passion for urban planning and community management. As disappointing as it is, the last possibility is probably the most plausible: Wilson was a friend of a friend of a friend who was just able to help out at the right time. One of those friends was likely to have been Wilson’s editor, Alfred George Gardiner whose firm roots at both Toynbee Hall and the Society of Friends of Russia — not to mention his recent election to the board of the Russian Relief Fund — would have made him fairly incumbent to the very people who had arranged Lenin’s and Gapon’s stay in London that year. Outside the tight-knit circle of revolutionaries, Lenin was practically unknown. The ‘celebrities’ at this time were the likes of Prince Kropotkin, Feliks Volkhovsky and the new ‘A-Lister’, Father Georgy Gapon. Lenin’s impact on the Brits was by contrast, a more understated affair. In fact it’s probably fairer to say that he didn’t appear on the radar at all. He was just another swarthy-looking gent skulking around East London in an incongruous fedora hat. Whatever he was, Philip Whitwell Wilson remains a curiously enigmatic character in one of the most profound and direct periods of the early 21st Century — a man playing a marginal role right at the centre of major developments.

Endnotes

1 Memories Of Lenin, Nadezhda Krupskaya, India Publishers, ed. Eric Verney, 1930, p.99

2 Memories of Lenin, Nadezhda Krupskaya, India Publishers, 1930, Chapter VIII, Nineteen Five in Emigration, pp.98-105, ed. Eric Verney.

3 Ленин в Лондоне/Lenin in London, Natalia Borisovna Karachan, Пособие для студентов педагогических институтов (на английском языке), 1969, p.37/The Spark That Lit the Revolution, Robert Henderson, I.B Tauris, 2020, p.128

4 Lenin and the British Museum Library, Solanus Volume 4, p.3, Bob Henderson

5 Electoral Register 1905-06 (England & Wales, Electoral Registers 1832-1932, Archive reference: SPR.Mic.P.316/BL.F.1/4. The address also appears as the family home in birth announcements the Daily News (28 December 1904, p.1) and in the Globe (19 October 1906, p.9)

6 ‘South St Pancras, Mr P. Whitwell Wilson’, Daily News, Feb 10 1905, p.12

7 Granta was (and the still is) the literary journal produced by Cambridge University. It was founded by fellow Liberal and Punch contributor, R. C. Lehmann.

8 Manchester Guardian, 25 Feb 1905, p.9 Gorky had already been taken in for questioning over his role in the organisation of the Bloody Sunday demonstration and Gapon’s subsequent escape from Russia.

9 Memories of Lenin, Nadezhda Krupskaya, India Publishers, 1930, Chapter VIII, Nineteen Five in Emigration, p.89, ed. Eric Verney.

10 A Militant Agreement for the Uprising and V. I. Lenin The Third Congress of the R.S.D.L.P, Vperyod, No. 7, February 21 (8), 19O5, Lenin

11 ‘Russian Nonconformists: Dr Soskice Interviewed’, London Daily News, May 2 1905, p.6

12 ‘Gapon’s Visit to London’, Dundee Courier, May 1, 1905, p.4

13 ‘Mr V. Bourtseff, editor & punisher of Narodovaletz’, Народоволец, Issues 1–4, 1897, p.40 ; ‘Alleged Nihilist Plot: Russian Arrested in London’, Morning Post, December 17, 1897, p.7; M: Mi5’s First Spymaster, Andrew Cook, History Press, 2011, p.138

14 Ford Madox Ford: Volume I: The World Before the War, Max Saunders, OUP Oxford, 1996, p.218; ‘Notes & News’, The Woman’s Journal, Boston, Vol. XXXVI, August 5 1906, p.123

15 The Last Dissenter: H.N. Brailsford and His World, F.M. Leventhal, Clarendon Press, 2003, pp.61-62

16 The Golden Echo, Chatto & Windus, 1953, David Garnett

17 ‘Haverford Explosion’, Liverpool Daily Post, 14 July 1906, p.10; Intoxicated by Soap’, Daily Mirror, 5 July 1906, p.5

18 ‘The Russian Tragedy’, Rosa Luxemburg, Spartacus, No. 11, 1918, English trans, Selected Political Writings, ed. Robert Looker, New York, 1974, pp. 235-43

19 ‘Books of the Day, Father Gapon’s Story’, London Daily News, 27 Nov 1905, p.4

20 Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, Helen Rappaport, Random House, 2009, pp.70-71; The Spark that Lit the Revolution, Robert Henderson,, I.B Tauris, Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, pp.182-183

21 Report by Ratayev, Okhrana, Paris to Department of Police, St Petersburg, 24 February 1903, Fond 102. Other names in the report include Feliks Volkhovsky, Leon Goldenberg and Nikolai Tchaykovsky

22 ‘Bomb Explosion in St Petersburg’, The Times, March 13, 1905, p.6; ‘Charge of Fraudulently Obtaining a Passport’, May 23, 1905, p.8

23 The Last Dissenter: H.N. Brailsford and His World, F.M. Leventhal, Clarendon Press, 2003, p.52

24 ‘Russian Passports Case’, Manchester Courier, 07 June 1905, p.8; The Last Dissenter: H.N. Brailsford and His World, F.M. Leventhal, Clarendon Press, 2003, p.52

25 ‘House of Lords, Lord Lansdowne’, Manchester Evening News, 06 May, 1903, p.2

26 ‘Father Gapon’s End’, Manchester Guardian, April 23 1906, p.6; ‘How Father Gapon was Led to His Death’, New York Times, 07 November 1909, Magazine Section

27 ‘Russian Woman Comes to London to Dies’, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 15 October, 1911, p.3; Leeds Mercury 16 October 1911, p.3

28 ‘The Danger of Loose Gas Jets’, London Evening Standard, August 21, 1912, p.5

29 George Liffen gave his son the name Theophile, which is French-Swiss in origin and an unusual step for a man who appears to have been born in Great Yarmouth. George Theophile Tideswell Liffen served as Second Lieutenant in the Prince’s Own Regiment during the war that followed. The most famous Theophile during the period in which his son was born was Theophile Gautier.

30 ‘Brother of Father Gapon’, London Daily News, March 1906, p.12

31 ‘Father Gapon’s Brother Drowned’, Derby Daily Telegraph 13 March 1906, p.3; ‘Hotel Mystery’, Dundee Evening Telegraph, March 21, 1906, p4 (newspaper reports Krebel’s body was discovered on Wednesday 13th March, 1906, a few days after checking in at the Liffen’s Hotel)

32 ‘Comedy in Hastings’, Daily News (London), January 27, 1905, p.6

33 ‘Russian Spies in Paris’, New York Times, February 16, 1905, p.8; Vladimir Burtsev and the Struggle for a Free Russia, Robert Henderson, Bloomsbury Academic, 2017, pp.116-117.

34 ‘General Trepoff’, The Times, Jan 26, 1905, p.4

35 Vladimir L’vovich Burtsev (1862-1942) was a Russian Revolutionary exile in London closely associated with Teplov’s Free Russian Library, the Free Russia press and the Society of Friends of Russia and well noted for his sensational skills in exposing Tsarist spies.

36 ‘The Crisis in Russia’, Aberdeen Press and Journal, 28 January 1905, p.5

37 Alexei Sheftel was a young Ukrainian typesetter whose name appeared alongside those of several notable Russian Socialist Revolutionaries in petitions of this period. He appears to have worked for Burfield & Pennells Ltd (47-49 Priory Street) printers of Jaakoff Prelooker’s popular émigré journal, The Anglo Russian Press. Sheftel immigrated to America in 1907, shortly after the kidnap of the daughter of the former Tsarist Police Chief A. Lopukhin in London in October 1907. She had been lodging with her governess in nearby Bexhill-on-Sea.

38 ‘Much to be Praised’, Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 17 March 1906, p.10

39 ‘A National Anti-Socialist League’, Pall Mall Gazette, 15 March 1906, p.9

40 Security Service Organisation, 1918-1939 Reports of the Secret Service Committee, File KV4/151, National Archives. The First Secret Service Committee consisted of Lord Curzon (Chairman), Sir Walter Long (Admiralty), Mr Edward Shortt (Home Office), Lord Peel (War Office) and Mr Macpherson (Irish Office)

41 ‘Russian Spies in Paris’, New York Times, February 16, 1905, p.8; ‘Russian Spies in Europe, How the Czar’s Secret Service Is Organized in Paris and London’, Daily Express, March 5, 1905, p.15

42 Vladimir Burtsev and the Russian revolutionary emigration: surveillance of foreign political refugees in London, 1891-1905, Henderson, Robert, Queen Mary, University of London. PhD Thesis, pp.238-239/The Daily Express, 16 February 1905, p. 4: `Russian Spies in Europe – How the Czar’s Police is organised in Paris and London’.

43 ‘The Stage from the Stalls’, The Sketch, 27 December 1905, p.14

44 General Evangeline Booth, P. Whitwell Wilson, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1934

45 The Settlement Ideal, Philip Whitwell Wilson, The Religious Life of London, Richard Mudie-Smith, Hodder and Stoughton, 1904, pp.294-301

46 The Barnetts of Toynbee Hall, Philip Whitwell Wilson, The Outlook, November 12, 1919, p. 306

47 ‘Russian Revolutionaries in London, A Relief Fund’, Aberdeen Press & Journal, January 28 1905, p.5. There was quite an enduring link between Oxford’s Balliol College, Toynbee Hall and the Society of Friends of Russia. Both Gardiner’s co-fundraiser George Meredith and Toynbee Hall director, Dean Robinson were senior figures at Balliol House. Lenin’s 1902 lecture at Liberty Hall was organised by Alexei Teplov, curator of the Free Russian Library, which had been located practically opposite Toynbee Hall.

48 The Spark That Lit the Revolution, Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, Robert Henderson, p.94

49 Conspirator, Helen Rappaport, Random House, 2010, p.110-111

50 ‘Russian Revolutionary Societies: Secret Sources of Information’, London Evening Standard 28 April 1905, p.12

51 ‘Russian Revolutionary Societies: Their Aims and Methods’, London Evening Standard 26 April 1905, p.2

52 World War I Draft Registration Cards 1917-1918, NARA series M1509

53 ‘Revolutionary Sherlock Holmes’, Vladimir Burtsev would have been the most obvious source of the story. I believe the Revolutionary Committee referred to is the Central Committee which featured Kropotkin, Natanson, Gots, Chernov and Zenzinov.

54 ‘Russian Revolutionary Societies: Secret Sources of Information’, London Evening Standard 28 April, 1905, p.8

55 ‘Russian Revolutionary Societies: Their Aims and Methods’, London Evening Standard 26 April 1905, p.2

56 Boston Sunday Globe, 26 August 1900, p.17

57 Globe 02 April 1906, p.8

58 The Pacific Century, America and Asia in a Changing World, Frank Gibney, C. Scribner’s Sons, 1993, p.53

59 His Imperial Highness the Grand Duke Alexis in the United States of America During the Winter of 1871-72, Riverside Press, 1872, p.52

60 St Andrews Citizen, May 1st 1909

61 The Spark That Lit the Revolution, Robert Henderson, I.B Tauris, 2020, pp.128-132.

62 Charles Masterman and Wilson were both residents at the Toynbee Hall ‘settlement’ project where Lenin addressed some meetings. In 1901 Masterman, Wilson and several other Toynbee Liberals put together a proposal for social and administrative reform (housing, transport and town planning). See: Unemployment and Politics; a Study in English Social Policy, 1886-1914. José Harris, Clarendon Press, 1972, p.213.

63 Wilson arrived in New York on the SS Baltic on January 2nd 1918.

64 The Thirty-Nine Steps, John Buchan, Oxford University Press, 1999, eds. Christopher Harvie, Christopher T. Harvie, Introduction, Xiii

65 ‘P.W.W’s Impressions of New York’, London Daily News, January 5 1918, p.1. The former British Ambassador in the US, Lord Bryce had served alongside Wilson on the Balkan Committee and was a key figure in the wartime propaganda bureaus and the Union of the League of Nations. Wilson had been a crucial press figure in Bryce’s Armenian support efforts.

66 ‘The English-Speaking League’, P.W. Wilson, The American Review of Reviews 1918-07: Vol. 58 Issue 1, pp.73-75

Alan Sargeant, October 2018:

https://independent.academia.edu/alansargeant

Who is Philip Whitwell Wilson?

- Born in Kendal in the county of Westmorland in 1876 to Isaac Whitwell Wilson, wealthy woollen manufacturer (b.1833). His grandfather John Jowitt Wilson had served as Justice of the Peace.

- Maths graduate of Cambridge and former president of the Cambridge Union Society.

- April 1899, marries Alice Selina Collins at Central Falls Congregational Church in Rhode Island, near Boston. She is the daughter of Henry Collins.

- Makes an incendiary address to the Liberal & Radical Association on the abuse of Chinese Labour (Slavery) in mines in South Africa (p.7 Shoreditch Observer 28 October 1905)

- As a Radical and Liberal MP for St Pancras South from 1906-1910 he enjoyed the support and confidence of many Labour organisations.

- Introduces the first Unemployed Workmen’s Compensation Bill into Parliament.

Related to Industrialist and Liberal MP Isaac Wilson (director of the Stockton and Darlington Railway) - Journalist for the left-wing Daily News (1907-1917) founded by Charles Dickens and owned at this time by George Cadbury. Its editor was Alfred George Gardiner. Serves on the paper from 1910 as Parliamentary Columnist.

- Stands as Liberal candidate for Appleby in Westmorland in December 1910.

- Council member for Whitefield’s Central Mission, Tottenham Court Road.

1912 sees the publication of Wilson’s The Beginnings of Modern Ireland. Published by Maunsell & Company, owned by Belfast publisher, actor and Celtic Revivalist/Gaelic League supporter George Roberts. - In April 1915 he publishes, ‘The Unmaking of Europe’, an uncompromising take on the first five months of the war and the motivations for the war.

October 1915, War and the Social Revolution is published. - In January 1918 he becomes American correspondent for the Daily News before moving to the New York Times.

- 1920 sees the American publication of Wilson’s The Irish Case before the Court of Public Opinion. Published by Boston Unitarian, D.L Moody’s Fleming H. Revell Company.

- In 1927 he publishes the Greville Memoirs (based on the politically scandalous diaries of Charles Cavendish Fulke Greville)

- Dies in New York in 1956.

War and Social Revolution (Philip Whitwell Wilson, The Fortnightly Review, October 1915)

- Although clearly owing a great deal of debt to Harry Quelch’s 1909 lecture of the same name, Wilson takes adopts a curiously Victor Grayson-esque take on the war’s impact on the ongoing Social Revolution. In fact, it’s difficult at times to know whether he is backing the war simply on the basis that it will eventually destroy the very capitalist system it props up, or whether he is experiencing the same fears as Quelch about the burden it will heap on the working class. So on balance, it’s fairly balanced. It’s an ‘everybody’s a winner, everybody’s a loser’ kind of thing.Here is the basic gist:

- Wilson forecasts the social and industrial problems that are bound to arise as soon as war finishes, and which have arisen in part as a result of inequalities and dissatisfaction among Britain’s workers. He addresses the war’s worrying impact on transport and the coal trade at a time of National Emergency. Says the scale of upheaval are “all the more formidable because its causes are obscure and its range incalculable.”

- Wilson suggests that some of these “obscure causes” were defective education (‘chronic evils, still un-remedied’) and volatile conditions in South Wale coal mines which bred fault on both sides (meddling trade unions etc).

- Repeats Lenin’s belief that real change comes with the desire not to just revolt but the will to organise and govern.

- Addresses the ‘mysterious disaffection’ experienced by working men and women despite the very real progress made in provision. Says that although progress has been made existing legislation was ‘inadequate’. Describes it as ‘ambulance work’ providing solutions and relief to only the most desperate cases. These changes ‘scarcely modified the status quo’. The ‘rewards when converted into coin, left little change at the end of the week.’

- Wilson leaves some criticism for the hyperbole of the press, aggravating the situation by sensationalizing the greed and waste of a disconnected London ‘regime’.

- Interestingly he talks of a very private conversation with Lord Nathaniel Rothschild. He says Rothschild was of the opinion that the war would give the working man bargaining power (through scarcity of labour as a result of enlistment). This would lead to an increase in wages.

Wilson talks of enlistment into the armed forces as a ‘leveller’. It gives rise to closer contact between the class extremes, and to the blurring of boundaries (and taken to its logical conclusion, the complete erosion of British class structures over time). - Wilson posits that it will be impossible to ‘renew the old fabrics of industry’ after the war. Men will not want to go back to their old ways. They will demand a voice (maverick Socialist MP Victor Grayson said much the same thing in his lectures in New Zealand prior to enlisting, repeating Lenin’s belief that it could train and prepare men for the revolution that would follow the war). As Wilson says, “To turn swords back into ploughshares will be a formidable task, but far more delicate will be the handling of immense bodies of men whose minds have been unsettled by the collapse of the old regime and by their one hour of glorious life.”The article is a well-balanced, cautionary tale warning of an ‘artificial boom and bust’ for the working man and the unemployment and desperation that might well follow.Unusually Wilson looks to the economic rebuilding opportunities the war will bring: “the reconstruction of devastated areas must be as boldly financed as the war itself” Indemnities “will take years to clear off … loans must be made in the form of houses and goods for Belgium, Poland, Serbia, and the French Provinces.” Warning or endorsement? It’s really very difficult to tell.

In view of the work of his friend, Charles Masterman at the War Propaganda Bureau, it might be reasonable to speculate that like Grayson, Wilson was quietly transforming the arguments of Social Justice into the arguments for war. But in fairness, it’s far from obvious.

you may also like reading:

Lenin @ 6 Oakley Square — 1911

https://pixelsurgery.wordpress.com/2015/11/11/lenins-london-oakley-square/

Lenin @ 21 Tavistock Place — 1908

https://pixelsurgery.wordpress.com/2011/11/14/lenin-tavistock/

Lenin @ 30 Holford Square— 1902

https://pixelsurgery.wordpress.com/2011/11/22/holford-square/

‘Traitors Within’, 1933 Herbert T. Fitch

‘The East End Years: A Stepney Childhood’, Freedom Press, 1998, Fermin Rocker

‘War and the Social Revolution’, Fortnightly Review, April 1915, Philip Whitewell Wilson

Lenin and the British Museum Library, Solanus Volume 4, p.3, Bob Henderson

‘Memories of Lenin’, 1933, Nadezhda Krupskaya

The Tsarist Secret Police and Russian Society, 1880-1917, New York University Press, 1996, Fredric S. Zuckerman

Letters from Brailsford to Soskice, 1905, Soskice Papers, SH/DS/1/BRA/22

Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, Helen Rappaport, 2009

The War and the Social Revolution, Philip Whitwell Wilson, Fortnightly Review, October 1915

The Story of My Life , Georgy Gapon, Strand Magazine, Vol 30, Issue 175, July 1905

Mr Brailsford’s Motives, Manchester Guardian, 05 August 1905, p.09

http://spartacus-educational.com/RUSgapon.htm

4 Comments Add yours